Article by guest blogger Dr Gerardo Poli

As a veterinarian in the field of emergency and critical care, the team and I rarely get to perform an anaesthesia that is planned in advance as often our patients are unstable or have significant underlying disease. We are therefore always mindful and prepared for the worst even with the seemingly normal or routine anaesthesia.

Below is a list of things to consider. If you get to the end and you find yourself not needing to make any changes then that is awesome and I send you a high five! If not, take it to your team to discuss!

Assuming a healthy patient is a low risk:

The individual’s anaesthesia risk is based on the patient history, physical examination findings, pre-anaesthestic blood tests and current disease states, but this does not account for different ways that patients can respond or comorbidities that have not been identified which can significantly increase anaesthesia risk. Therefore each patient should be considered at risk for an adverse event and monitored at an appropriate baseline level (beyond the scope of this article) but if a patient is older, has known pre-existing health problems then their level of monitoring must be phased up appropriately from the baseline.

Recovery phase does not mean the job is done:

The recovery phase is the where most anaesthesia related deaths occur. Make sure that as part of the anaesthesia plan there is a plan for the recovery phase. We often think our patients are out of the high-risk phase because they are now waking up, but that is incorrect and often the level of monitoring needs to be leveled up. Things to consider to make this phase safer and more efficient:

- Where is my patient going to recover and what will I need, eg. active warming equipment?

- What post-anaesthesia monitoring is required for the patient, eg. blood pressure, ECG…?

- Who is going to monitor my patient and are they ready?

- What medications are required post-operatively eg. pain relief, antibiotics?

- What blood tests need to be repeated, eg. packed cell volume or coagulation times?

- What fluid rate do I continue my patient on?

Anaesthesia records:

Anaesthetic records are incredibly important, I sometimes get frustrated with having to fill them in but I have to remind myself of the important role they play in troubleshooting if things go wrong, not only that it is a legal requirement. Here are some things to consider.

- Is there sufficient patient detail to be able to identify who the chart belongs too?

- Pre-anaesthesia vitals are important as you can pick up things that weren’t there beforehand, or things that should have been corrected but remain persistent eg. Tachycardia which should have been resolved with either pain relief or IV fluids, maybe that patient needs more stabilising before anaesthesia.

- Recording vitals during the anaesthesia is also important and depends on what monitoring equipment you have available but trends are more easily identified when seen visually than with just numbers.

- Record all drugs that were given, when and how much and in milligrams and by what route.

- Record any adverse events and what changes were made to the anaesthesia.

- Finally check your local state or government requirements on how long you need to store them for (either physically or digitally) for legal purposes.

Use more analgesia, not more anaesthesia:

Briefly, anaesthesia is the lack of sensation and analgesia is the lack of pain. The reason for why it is important to differentiate this is that most anaesthetic agents do not provide pain relief. Using them at at high doses to suppress a patients awareness or physiological changes, is not an appropriate way to address pain. Increasing anaesthesia is often more dangerous than titrating additional smaller IV doses of an opiate. Opiates are the most common analgesic and they have minimal cardiovascular effects compared to anaesthetic gas when used at appropriate doses. High levels of anaesthetic agents are the most frequent cause of hypotension in anaesthetised patients. At our hospital we ride our anaesthetic gas quite low (often below 1%) and we achieve this through the use of opiates which reduce the minimum alveolar anaesthetic concentration (MAC). So the question you should ask yourself is… “Does my patient need more pain relief?”, not “Should I turn up the gas or provide more anaesthesia”.

Anaesthesia checklists save time and stress:

Checklists can increase efficiency, reduce stress, enable you to be prepared for emergencies and also save lives. Consider checklists for:

- Pre-anaesthesia patient checks – IV catheter is patent, reassess patient vitals, blood pressure, current pain score.

- Setting up and checking the anaesthetic machine and CO2 absorbents.

- Setting up the surgery for the procedure – What do you think you need? Gathering this information can reduce anaesthetic time and therefore patient risk.

- Checklist of questions to ask the vet:

- What is the procedure that we are doing?

- What equipment or supplies do we need?

- Does the pet have any comorbidities that have not been communicated?

- Is the patient on any long term medications?

- Do you have any concerns regarding the patients suitability for the anaesthesia, also what anaesthesia risk grading is the patient?

- Does the patient need any medications prior to anaesthesia? When was the premedication given? Does it need additional paint relief?

- What are the contingencies if hypotension occurs? What is the first level of intervention?

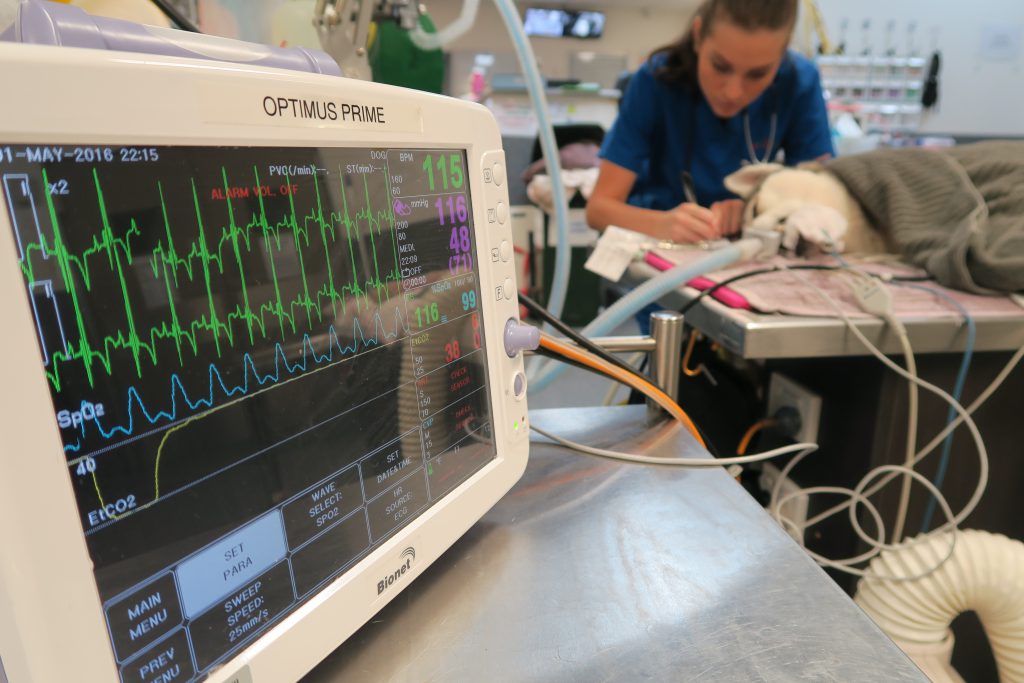

Monitor the patient, not the monitor

We can spend significant time looking at monitors that give us an indication of how the patient is going but we have to make sure we actually assess the patient. The monitors don’t give us a complete picture. Make sure you have access to the patient; can you check pulses (lingual if need be), mucous membrane colour, capillary refill time and record those as part of anaesthetic monitoring. A classic example is a electromechanical dissociation where the ECG can look normal but the heart is not actually beating.

Have algorithms to manage hypotension…

When an emergency happens you can’t rely on being calm and having the mental capacity to think things through. So it is important to set yourself up for success at the start. Consider having checklists, pre-prepared kits and algorithms ready.

- Hypotension algorithm: Have it on the wall in theatre so that you can work through it when it occurs.

- Fluid bolus kit: If you need to give an IV fluid bolus quickly, a 1L bag of Hartmanns, 18g needle and 50ml syringe.

- Vasopressor kits: We have a dopamine CRI kit which contains a CRI chart, instructions on how to make it up, 500ml bag of saline, giving set, a vial of dopamine, 10ml syringe and needle, label etc.

- CPR kit: CPR algorithm, adrenaline and atropine drawn up, an assortment of needles and syringes.

Manage hypothermia before it even occurs …

Being proactive in the management of hypothermia. Hypothermia needs to be tackled as soon as the patient is anaesthetised, as once they are hypothermic it is hard to reverse it. Why is hypothermia a problem?

- Prolongs patient recovery

- Reduces the ability of the cardiovascular system to respond to compensatory mechanisms to hypotension

- Suppresses the immune system

- Prolongs the metabolism of drugs that have been administered

Strategies to help prevent hypothermia include but are not limited to:

- Covering up patients once anaesthetised

- Reducing anaesthesia time

- Warming lavage fluids

- Circulating warm air or water blankets

- Inspired air warmers

- Avoid electric heating pads – they can cause heat burns

I hope this was helpful and stimulated thoughts and discussions on how to make anaesthesia safer in your hospital.

DR GERARDO POLI (Hons class 1)

Masters Veterinary Studies (Small Animal Practice)

MANZCVSc (Emergency and Critical Care)

@drgerardopoli

Gerardo is an Emergency Veterinarian and Company Director at the Animal Emergency Service, Australia. Gerardo joined the Underwood team in 2010. He achieved Membership with the Australian and New Zealand College of Veterinary Scientists in the field of Emergency and Critical Care in 2012, and was head examiner for future Membership candidates for 3 years. In 2014 he completed his Masters of Veterinary Studies in Small Animal Practice through Murdoch University, which focuses on the more advanced aspects of small animal medicine. Gerardo has a strong interest in the stabilisation and management of critically ill patients, small animal ultrasound and radiology, emergency surgery and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. He lectures around Australia and internationally on these topics and is the coordinator of the AES Accelerate program which is a course designed to fast track a veterinarians transition into the field of Emergency and Critical Care.